Of all the tactile pleasures I can think of, interacting with paper is among my favorites. Paper is as varied as food: slick-coated candied magazines, paperbacks with soft pastry pages, hot white copies sizzling with toner, tea-colored lines steeping secrets in a journal. There is no repulsive paper.

I spent years drawing, folding, writing, painting, rolling, and preserving paper before it ever really occurred to me to cut. In graduate school I eagerly signed up for Art of the Book. Cutting signatures and stitching bindings was worth the cold reality of 8 am class. One of our first lessons was how to make a simple 16-page accordion book out of one sheet of paper.

That did me in. A single page was transformed into a book with a few folds and snips. It's not the most elegant kind of book, but this change into a new object had me hooked. What else could be done with a single sheet?

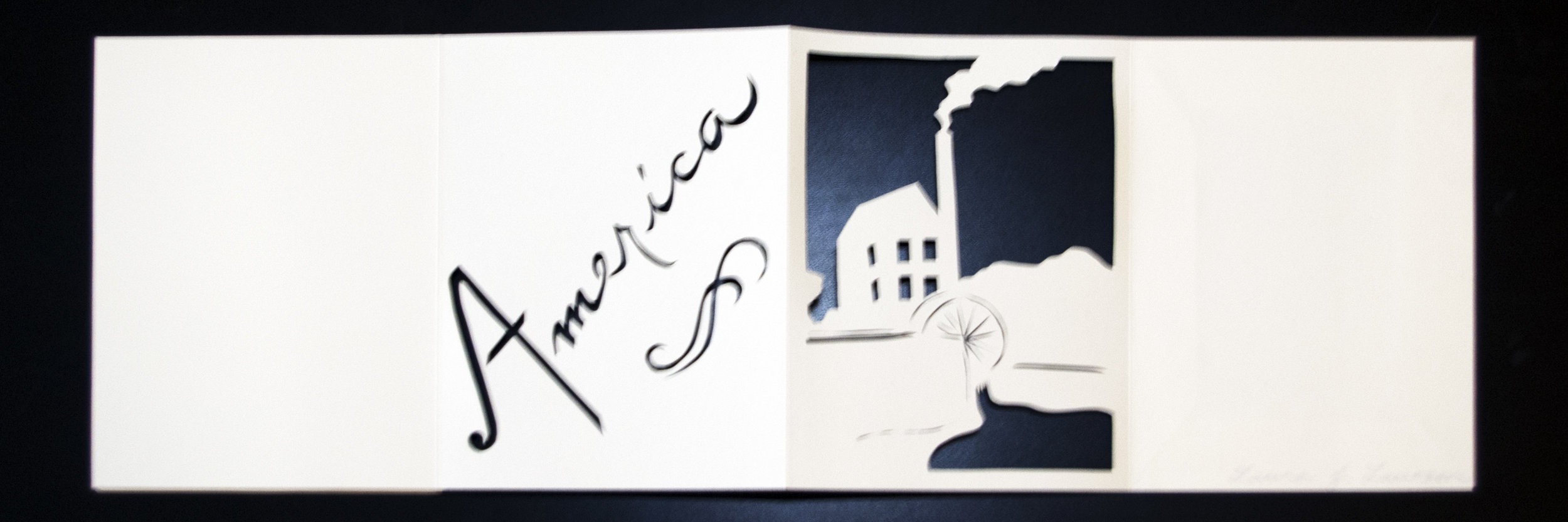

I can't remember the guidelines for our first project, but I could not let go of the idea of the single sheet transformed. I wanted to go beyond making content with pencil or ink. The pages alone had to carry their weight. So, I cut into them.

To express something big in a modest project, I chose to illustrate the use of paper across continents and time. Of course, this is an extremely long and varied history-- far too complex to really explain in a picture book-- so I picked four places to highlight.

After folding and cutting a sheet of drawing paper into the accordion book, I found that the structure of the paper would allow me four two-page layouts. Rather than pack in eight places with questionable identity, I chose to work in the style and language the paper was used for.

A real historian of paper might have some advice on locations, and native readers of Mandarin and Arabic may have some corrections for me, but I was more concerned with my due date. The four places I settled on were China, Iran, Germany, and the United States. The written titles are a bit more generic: I opted for something like "the Islamic world," as well as Europe and America.

It's not a perfect project by any means, but unpacking it recently was a welcome surprise. It's a clear link between my past and current work. I did a few other projects where I cut my own drawings, but doing this piece ultimately led me to cutting up maps to explore my biggest obsession-- the human experience of place. Erasure by knife and the transformation of the object created a huge breakthrough for me, and over 100 X-Acto blades later, I'm still making discoveries with it. I'm excited to see what comes next.